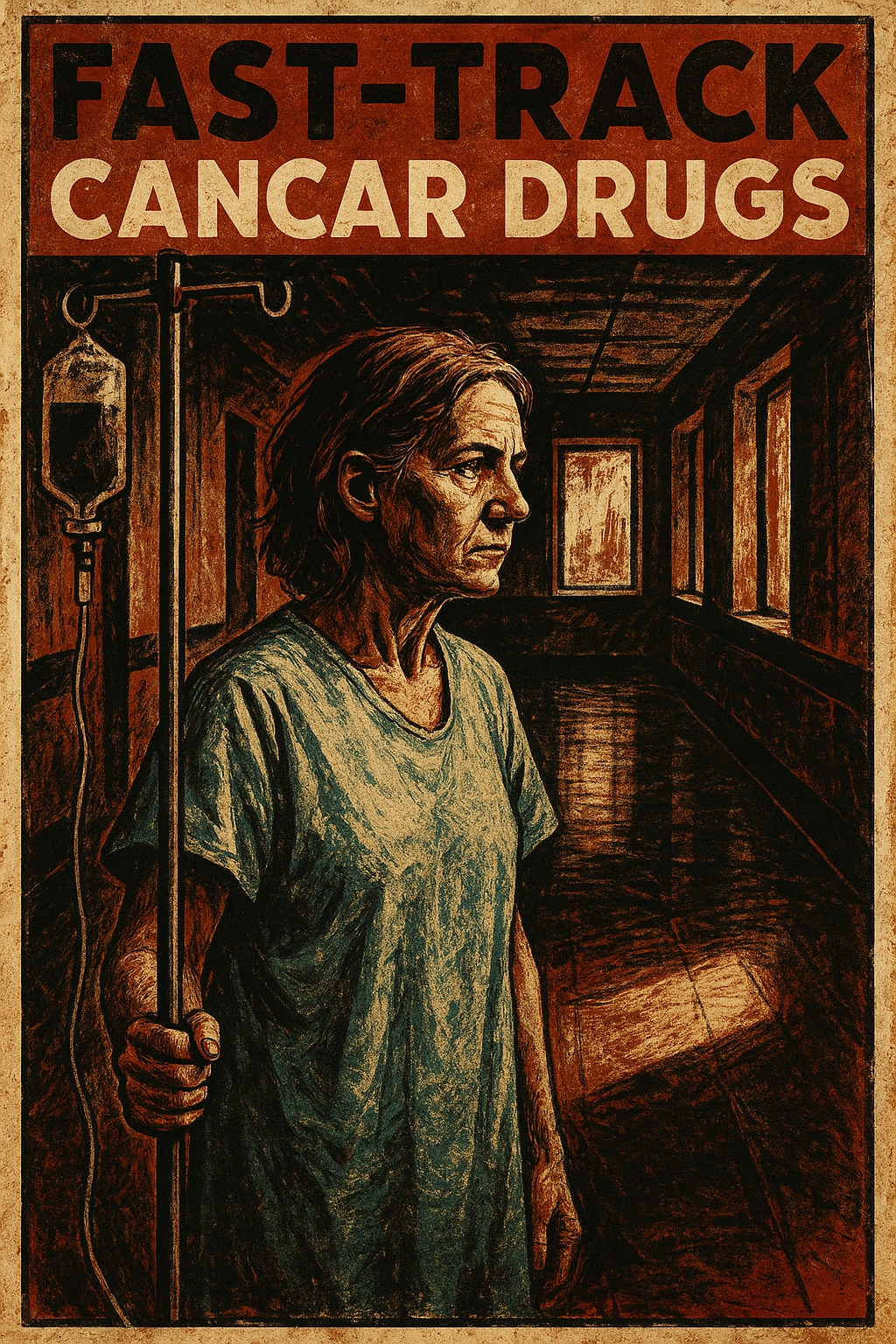

Ontario’s Fast-Track Cancer Drug Program Promises Faster Care — and Raises Questions About Equity and Cost

Share

October 2025 marks a turning point for Ontario’s healthcare system as the province launches an ambitious initiative to speed up access to cancer medications that could save lives. The Accelerated Access Program (AAP), announced by Health Minister Sylvia Jones, aims to shorten the time between federal approval and patient treatment for new cancer drugs — from nearly a year to just a few weeks.

Officials say the move could redefine cancer care for thousands of Ontarians, particularly those facing advanced-stage diagnoses where every week matters.

A Growing Urgency

Cancer remains Ontario’s leading cause of death, with over 90,000 new cases expected in 2025, according to Cancer Care Ontario. Common cancers such as breast, lung, and colorectal are driving the majority of diagnoses. Yet access to next-generation therapies — such as immunotherapies and precision-targeted treatments — has often been hampered by lengthy regulatory and funding delays.

The AAP, introduced in September 2025, builds on lessons from the COVID-19 vaccine rollout. It allows for parallel assessments between Health Canada, the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), and Ontario Health, eliminating sequential review steps that used to take up to 18 months.

Under the new model, hospitals can access 30 high-priority cancer medications — including drugs like pembrolizumab and trastuzumab — within weeks of Health Canada’s green light. Ontario has allocated $200 million for 2025–2026 to fund the program’s first phase.

How It Works

Previously, new cancer drugs followed a long path: Health Canada approval, CADTH review, provincial negotiations, and final funding authorization. The AAP condenses this process through a joint provincial-federal task force that conducts assessments simultaneously. Once approved, funding flows from a dedicated provincial pool, removing the need for hospital-by-hospital budget requests.

During a pilot phase between June and August 2025, more than 1,200 patients received access to 12 drugs with average wait times of just 21 days, down from nearly six months under the prior system. Specialists like Dr. Lillian Siu at Toronto’s Princess Margaret Cancer Centre have called the shift “a paradigm change,” particularly for patients who previously had limited treatment options.

Impact Across the System

The new framework is also reshaping hospital operations. Oncology units at Sunnybrook and Juravinski Cancer Centre are expanding infusion capacity and hiring new staff, adding an estimated 300 jobs this year alone. Smaller community pharmacies near cancer centres are reporting an uptick in demand for supportive care medications as patients begin treatment sooner.

Public sentiment is largely supportive. A Leger poll from September 2025 found 78% of Ontarians approve of the AAP’s goals, though 42% expressed concern about long-term affordability. Advocacy groups have praised the policy as “a lifeline for families,” while rural and Indigenous communities have warned that uneven access could persist without targeted investment in remote healthcare infrastructure.

Challenges Ahead

Cost remains the largest unknown. Many of the therapies covered under the AAP — including biologics and cell-based treatments — cost $100,000 or more per patient each year. Critics, including opposition health critics from the Ontario NDP, argue that the province may be prioritizing drug funding at the expense of under-resourced primary care systems.

Access equity is another concern. Hospitals in Thunder Bay and Kingston have reported delays in recruiting oncology staff, and First Nations health authorities have urged the province to include dedicated transportation and outreach supports in the next budget cycle.

There are also national implications. Ontario’s unilateral approach has sparked tension with other provinces, some of which rely on slower, pan-Canadian funding models. Meanwhile, pharmaceutical companies are closely monitoring pricing discussions, with the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board already reviewing potential price adjustments.

A Measured Step Forward

Despite these challenges, the AAP represents a significant shift in how Canada approaches life-saving treatments. For patients like Sarah M., a 42-year-old mother from Ottawa living with triple-negative breast cancer, the new system meant starting immunotherapy just 15 days after recommendation — a delay that would once have stretched half a year.

Stories like hers are already circulating online under the hashtag #FastTrackCancer, turning policy into personal testimony. The Ontario government plans to review the program’s outcomes in mid-2026, with potential expansion to pediatric and rare cancers depending on performance data.

If successful, the model could influence national health policy and serve as a blueprint for other provinces navigating the balance between innovation, cost, and access. For now, the message from Queen’s Park is clear: Ontario intends to make time a patient’s ally rather than their enemy.